A writer never knows when her next story will present itself and get the creative juices flowing. In fact, sometimes the inspiration knocks not on the front door, but comes sneaking in the back when they’re wondering why in hell the doorbell rang if there’s no one there. Sometimes it comes when you’re sitting on the couch sipping wine with your best friend from college who suddenly announces, “Did I ever tell you I was babysat by a serial killer?” And sometimes it comes when you’re working on an entirely different project and a new one quietly says, “Ahem, excuse me, but I’m pretty damn fascinating too.”

That’s the story of how my second book, “Last Man on the Mountain: The Death of an American Adventurer on K2” (Norton, 2010), was born.

It was 2002, and was once again I was headed to Pakistan to sit at the base of its infamous K2, at 28,250 feet, the second highest mountain in the world, and arguably, among its deadliest. I wasn’t going to climb the behemoth; I was going back to the mountain to continue my research and to make a documentary about the women who had climbed and perished on its grueling slopes. My first trip in 2000 had been nothing short of disaster because the team seemed more suited to starring roles in “Beavis and Butthead” and “Lord of the Flies” than men and women able and ready to tackle a mountain of K2’s rigors. I didn’t know that when we all gathered at JFK for the flights to Islamabad, but I had a dim foreboding soon after when I saw the copious amounts of alcohol they consumed on an otherwise dry airliner – a direct slap in the face to the flight attendants on our Pakistan International Airways plane, owned and operated by an Islamic country. It only got worse from there, including my falling into a crevasse and being grateful that I had been with one of the few stand-up men on the team, and not one of the violent drunks who I feared would have left me to die in its icy caverns. I still have nightmares that he did.

Anyway, it was a horrible trip and yet two years later I once again packed my duffels and headed to back K2. But this time I was going with trusted and loving friends, strong climbers, and culturally-sensitive travelers. It also helped the expedition’s dynamic that we were going into the south side of K2, rather than the far more remote north side as I had in 2000. That journey into the mountain took nearly a month between the airport and base camp and included buses, jeeps, camels, and a final twelve miles trekking in on the Qogir glacier. The south side approach in contrast, involves a short and spectacular flight from Islamabad to Skardu which threads through the mountains, and flies so close to eight-thousand-meter Nanga Parbat you can see individual crevasses cutting high into the slopes. From Skardu, jeeps take you another several hours to the end of the road in the tiny village of Askole and from there you hoist your pack and start walking. Some seventy miles later, you’re at the base of the mountain. It sounds (and is) arduous, but compared to the north side of K2, it’s casual.

During our long summer on K2, the team worked to establish high camps on the mountain, stocked them with food and gear for their eventual (and hoped for) summit bid, and watched for rare breaks in the weather. While the team toiled to climb the mountain, I worked at its base emailing and faxing (!!) our film team back in Los Angeles, interviewing other climbers at base camp, writing the story board for our documentary, and outlining the book that would expand on the film’s theme of the first five women who climbed the mountain, all of whom were dead. Most days by lunchtime my “office” work was done and I would spend the afternoon exploring the glacial moraine which surrounds the mountain and stretches into all directions as far as the eye can see and the foot can travel. Because K2 is shaped like a pyramid – long, straight, nearly unbroken ridges and slopes – everything that was ever on the mountain, eventually ends up at its base, including scores of dead climbers and their battered gear. Having a good eye for detritus that doesn’t belong where it is, I frequently found debris of expeditions past, most of it benign pieces of clothing or gear, but some of it utterly gruesome – chips of human bones and skulls, a severed foot in a boot, a torso “climbing” out of the glacier, and once, an entire body perfectly preserved by the elements, right down to its toe and finger nails. As horrific as the finding was, it could have been worse – because of the brutality of falling thousands of feet, the head almost always detaches from the body (it is the weakest link, after all). We identified the climber through his clothing as one of those killed seven years earlier, in 1995, when he fell from just below the summit to its base nearly twelve thousand feet below. There, snow and ice had buried him every year while the summer sun then exposed him. We wrapped his body in a nearby tent fragment and lowered him into a crevasse, saying a prayer as we always did when “burying” K2’s dead. My findings were so regular that Hector Ponce de Leon, our team leader and dear friend, started calling me the bone collector.

Indeed.

A short couple of weeks later I was again poking around the glacier, this time accompanied by my partner Jeff Rhoads, when I came upon a debris field of gear I instantly recognized as being decades older than anything I’d previously found – bits of a canvas tent, a chunk of a thermal sleeping bag, a rusted tin cup, a stainless steel matchbook, a dented Primus stove, a length of hemp rope. And there, in the middle of it all, was a human skeleton. Well, enough of it to identify it as human – ribs, pelvic bones, and remnants of leg and arm bones – ulna, radius, humerus, femur, tibia, fibula. And again, thankfully, no head, although there was a shock of long, white hair. I called out to Jeff, who came trotting through the ice towers carrying a glove. Seems he had been doing his own scavenging. And on the glove was written a name: WOLFE.

“Holy shit,” I said. “I can’t believe we found him.”

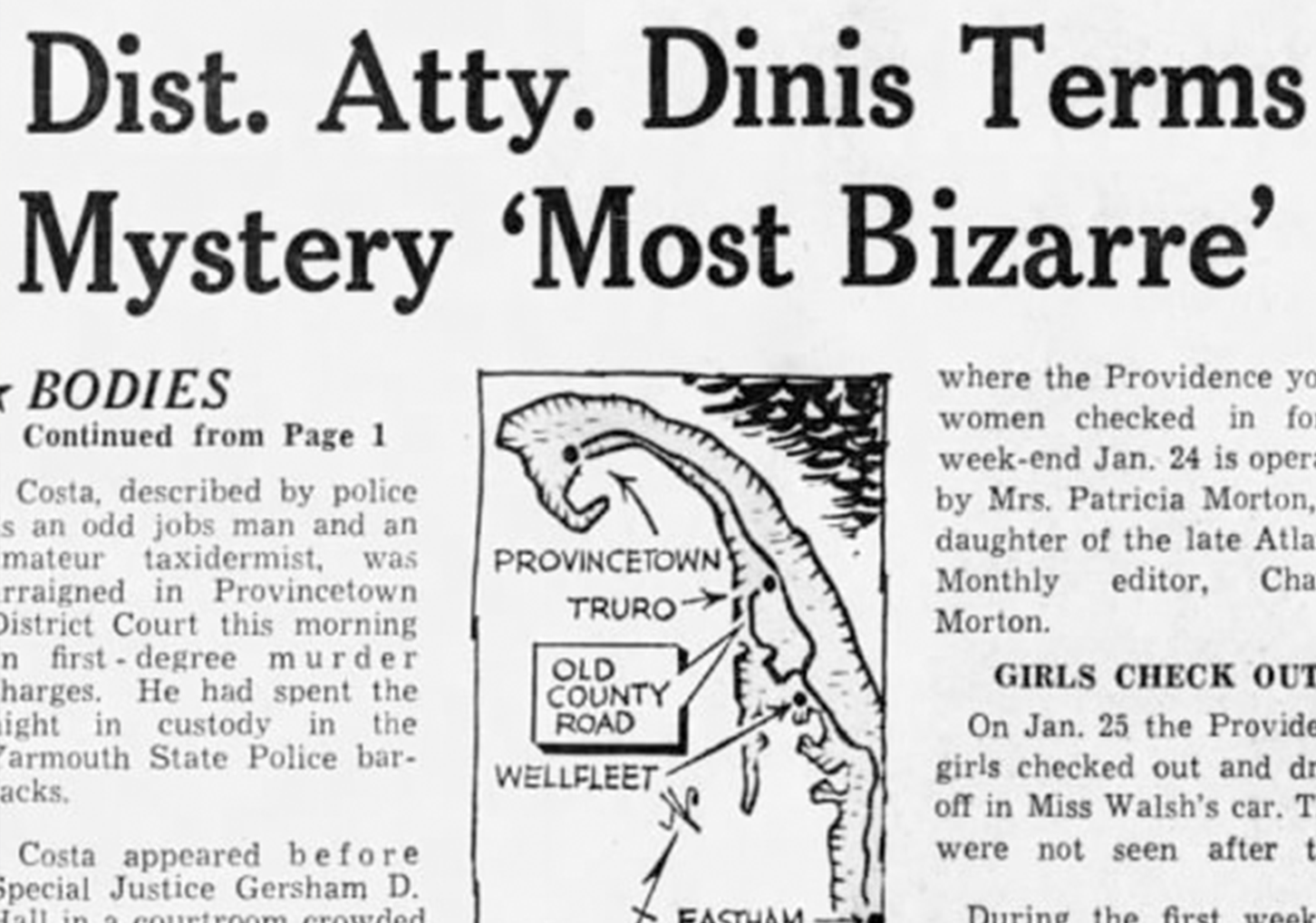

Dudley Francis Wolfe had been left for dead sixty three years earlier on the highest reaches of the mountain. He had climbed higher than any of his 1939 teammates besides their leader, Fritz Wiessner, but after five weeks in the so-called Death Zone above 25,000 feet, he hadn’t had the strength or the experience needed to get back down. Wiessner returned to the U.S. and, fearing condemnation for having abandoned a teammate, announced that Dudley had perished due to his own arrogance in climbing too high, that he had been “fat, lazy, and clumsy,” and, most damning of all, “a stubborn American millionaire” who had bought his way on the expedition and demanded to stay on the mountain until he had conquered the summit.

And over six decades later I sat in base camp, reading those defaming words while holding Dudley’s bones in my hands. Suddenly I looked up at the area where Wiessner had left him on the mountain, and thought, “Wait a minute. Arrogant and rich maybe, but no one gets there who is fat, lazy and clumsy,” especially without supplemental oxygen, Sherpas, and a lot of rope – none of which the 1939 team had.

“To the victor go the spoils.” Sure. But spoils are one thing. Now I knew history got the story wrong, that lie had become legend, and I was going to do something about it.

And I did; “Last Man on the Mountain” was published in 2010.

You just never know where your next inspiration will be found. But, I do hope you won’t have to travel half way around the world and to the base of a savage mountain to find it.

Jennifer Jordan

April 2022

Leave A Comment